|

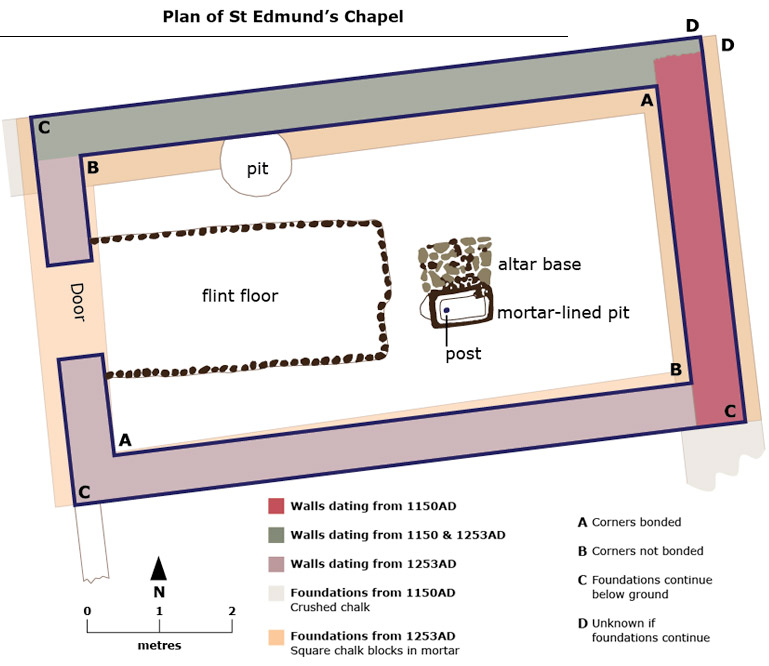

The Archaeological Dig Medieval Dover Dover Castle After the Norman Conquest much of Saxon Dover was rebuilt. The town benefited from the increase in cross channel trade and the carrying of passengers between France and England, stimulated by William the Conqueror. Great improvements were made to the castle. By 1190 the massive stone keep and inner walls or bailey surrounding it were complete. The thirteenth century saw many attacks on the town by French forces including the almost successful 1216 siege of the castle by Prince Louis and a great raid of 1295 when 10,000 French burnt most of Dover to the ground. The Cinque Ports In about 1050 the five ports of Dover, Sandwich, Hastings, Romney and Hythe joined together to provide ships and men for the King, Edward the Confessor. They became known as the Cinque Ports (after the French word for five, but always pronounced as 'sink' not 'sank'). In return for providing naval and ferry services these towns received many rights and privileges. Today the Cinque ports have only a ceremonial role, but locally a base for the Lord Warden of the Ports is still provided at Walmer Castle, and new Lords Warden are always installed at Dover. Dover's Churches After the Norman Conquest many new stone churches and religious houses were built. Much of Dover's medieval history concerns the various churches and religious houses which were established in and around the town. St. Mary's Church: St. Mary's Church is of early Norman origin built on the foundations of a Roman structure. The Maison Dieu: Founded in 1203 by Hubert de Burgh, the Maison Dieu was built as a hospice for pilgrims. Today it is part of Dover's Town Hall and is open to visitors. Dover Priory: Founded in 1130, Dover Priory was dedicated to St. Martin and intended to house Augustinian monks. Henry VIII confiscated the land and buildings which became a farm. Today it houses Dover College, a private school. St-Martin-le-Grand Church: Commenced around 1070 at a site on the western side of the present Market Square. Building work seems to have stopped at the beginning of the twelfth century. In 1130 King Henry I was finally persuaded to grant the church and all its estates to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Archbishop originally planned to complete the church and use it for the new order, but the monks of Canterbury did not like this, and in 1139 they managed to persuade him to build a new house just outside Dover which became St Martins Priory. The church, later called St-Martin-le-Grand, was eventually completed. back to top of page >> St Edmund's Chapel While most of what we know of the structure and architecture of the Chapel has been discovered through Mr Swaine, the rest has been learned from Mr Brian Philp, A.C.C.S. The interior measurements of the Chapel are 26 ft 9 in. x 14 ft, or 375 sq. ft. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the smallest Church in regular use in England is at Culborne, Somerset. It measures 420 sq. ft. If this is reliable evidence, St Edmund's Chapel is now the smallest Church in regular use in England. There are two smaller: at Upleatham, Yorkshire (230 sq. ft.), and Lullington near Alfriston, Sussex (256 sq. ft.), but the one is not now used, and the other only used occasionally. |

|

|

When the Chapel was being restored, it was considered possible that the 'bowels of St Richard' had been placed in an urn or wooden box or leather bag since it was obvious that Ralph Bocking had considered them a precious relic. It was decided therefore, to invite a team led by Brian Philp, the well-known Kent archaeologist, to excavate the inside area of the Chapel. Many of the results appear elsewhere on this website but recorded here in some detail are those those which concern the relics of St Richard.

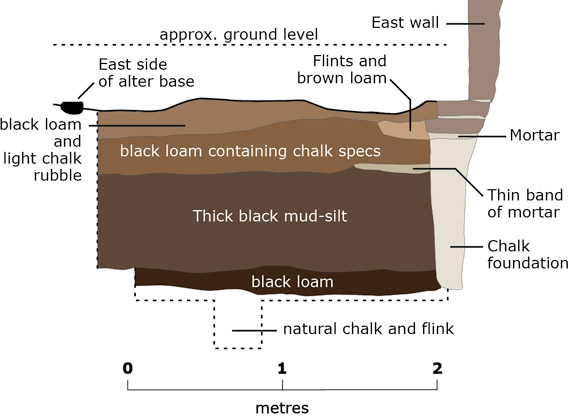

A priori, it was considered probable that the relic would have been buried near the altar. It was also thought that the altar would have been at the east end of the Chapel. The first excavation was, therefore, at the east end. This revealed a lot about the history of the Chapel, but although the dig went back, through the Roman level, to the undisturbed 'natural' level of the earth, no sign was found of anything to suggest thirteenth-century burial. The finds of this trial excavation were so interesting that the next days were taken up with further excavations to confirm and enlarge its findings. The base of the altar had now been located in the eastern half of the Chapel, more towards the middle than the eastern end.

It was only on the last day of the dig that excavations were made near the altar base. These revealed a small cist to the south side of the altar. The original 'hole' had been some thirty-four inches long, and some twenty-two inches wide. It had been dug into the earth without any dressing. The base was earth. The sides had then been roughly plastered with puddled chalk. this had simply been hand-pressed round the sides of the hole, about three inches thick. The resulting cavity had been filled in with loose earth from the thirteenth-century layer of the Chapel's soil, and covered with a layer of chalk and mortar. What led to the discovery of this cist was a round hole, three inches in diameter, at a very, very slight angle, inclining to the altar. This hole was found to be eleven inches in depth. Undoubtedly a wooden stake had originally been place in the loose earth of the cist and protruded out of the cist and touched the altar. The stake had rotted away. The cist was partially sealed by the base of the altar. It was very probably of thirteenth-century origin. It was certainly constructed to bury something. That 'thing' was important enough to merit a stake to indicate its exact position. Its position, at the base of the altar, indicates both the importance and the sacredness of what was buried. No mason was responsible for such a poor construction, which could suggest haste, consistent with a death and disembowelling. Read again what the eye-witness, Ralph Bocking, wrote: 'At this spot many favours were granted', and there seems no reasonable doubt that this is the spot where the bowels of St Richard were buried. No trace of an urn, a wooden box, or a leather bag was found. The slab of chalk and mortar which had covered the cist had prevented the loose earth inside from being subjected to any downward pressure, and when uncovered it was still remarkably loose. Had there been a container which in the course of time had rotted away, there would have been some settlement in this loose earth. The indications are, therefore, that this cist was prepared on the orders of Ralph Bocking and Simon of Tarring: that St Richard's bowels were reverently ('venerabiliter') deposited in it and covered with loose earth and that the cavity was then slabbed over. The question can be asked whether the stake was intended only 'to indicate the spot'? Ralph Bocking continues: As soon as his body, robed in his episcopal vestments, had been put in its coffin, a great crowd of people came from everywhere, to be present at the funeral of a man worthy of such veneration. That man was counted lucky who touched the coffin, or even the hem of the vestments, or who could touch with a ring or other ornament his face, hands, or feet. Whatever had touched the saint was considered to have been made holy and was kept as a relic. It would not have been extraordinary in the middle ages if this stake had been a way of 'touching the saint', on the principle that what you do by another, you yourself do. Strangely, there is corroboratory evidence that in the case of St Edmund that the Chapel where the bowels were buried was not without significance.

There is some evidence that the Chapel was slated in blue slate, since so much broken blue slate was found, both in the walls and in the builders' back-fill. This slate came from the south-western peninsula of England, and its use here and at Faversham would be the earliest examples of its known use in the south-east of England. The present roofing ties are probably a mixture from medieval and seventeenth-century roofs.In the thirteenth century the Sacrament would not have been reserved in a Cemetery Chapel. The installation of a tabernacle was the only concession to twentieth-century practice. However the inherent damp conditions in the chapel walls have rendered it unsuitable for its purpose and therefore it is no longer in use. |

|