|

A short life of St Richard of Chichester Feast Day: 3 April Little is known of the childhood of Richard de la Wyck, but the impression is strong that it was very different from the childhood of Edmund of Abingdon.

As they could not afford farm-workers, Richard ploughed, sowed, reaped and threshed until the farm was in good working order. Robert was so delighted that he made it over to his younger brother. It would imply that Robert had done little of the work himself. Richard was now an eligible bachelor, and friends and neighbours began to arrange his marriage to a young girl who was both rich and charming. This was rather more than Robert could bear, and there was obviously the beginning of an unpleasant scene which Richard cut short by saying that no woman was worth a row. He gave back the farm to Robert and offered him the girl (I've never kissed her on the lips') and went to Oxford to study. The medievals were fond of seeing auguries, especially in a name. Their auguries were often far-fetched, but they were not as far-fetched as usual when they read Richard's character into the name given him at his christening. Nominis in primo rides, dulcescis in imo; In Latin his name was Ricardus and the point of the couplet is RIdes, CARus, DUlececiS (You'll laugh, be loved of God and killed to your fellow-men); or, in English verse, as dubious as the Latin: At first your name suggets a smile. Richard did nothing by halves. Having given his brother the farm and the girl, he gave him whatever money there was as well. He went to Oxford penniless. He shared a room and a cloak with two other scholars: ate bread and soup with a little wine, except on Sundays and feast days, when he had some meat: met Edmund of Abingdon and Robert Grosseteste: and was launched on to the medieval scene.

There is no contemporary evidence that Richard went to Bologna, and the chronology of his life is certainly against it. Some sort of tradition about it developed, and Capgrave included this later tradition in his Life. It is included as he tells it, but with the warning that it is almost certainly an 'embroidery'. After Oxford, Richard went to Bologna for seven years to study Cannon Law. Towards the end of this time, his professor was taken ill and invited him to give the lectures in his place. He lectured for more than six months and rapidly gained a reputation as a lecturer. His professor was fond of him, and offered him his only daughter in marriage 'with all his land and property'. Richard made some excuse about having to return home, and left with a half-promise that he would be back. He never returned. He went to Oxford and, by unanimous consent, was offered the Chancellorship. Now, for the first time, we read of his nights of prayer and bodily penances, and his indecision in respect of marriage has been read as a sign that he was thinking of ordination. He had been Chancellor of Oxford University for two years when both Edmund of Abingdon, who had become Archbishop of Canterbury, and Robert Grosseteste, who had become Bishop of Lincoln, invited him to be their Chancellor. He accepted Edmund's invitation, and for the next six years was his constant companion. There is no doubt that he both liked and admired Edmund, and that during these years his prayers and penalties multiplied through Edmund's example and encouragement. Bocking was later to write: 'The Archbishop rejoiced that by the decision of his chancellor he was shielded from the intrusion of much of his day-to-day work: and the chancellor was glad to be taught by the holiness and conversation of his master. Each leaned upon the other - the saint upon the saint: the father on the son, and the son on the father.'

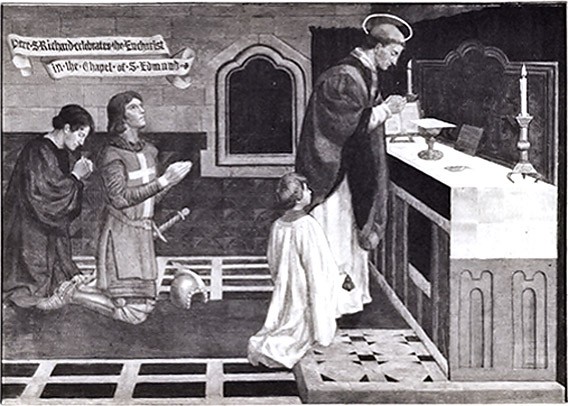

Richard accompanied Edmund on his journey to Rome and was with him when he died at Soisy. It was he who broke the Archbishop's seal as a sign that his reign was over. In his Will, Edmund bequeathed his goblet "to my beloved Chancellor, whom I have long and heartily loved'. It was this goblet that Richard later used to bless a crippled boy. He told the boy to drink from it and as he drank he was made whole. He now decided on ordination to the priesthood, and went to study theology for two years with the Dominicans at Orleans. He already venerated Edmund as a saint and built a small shrine to him before which he often prayed. At his ordination, he was dressed more simply that the others, and as a priest he wanted only a small parish where he could give himself to the cure of souls. He came as priest to Deal, Kent. It must have held memories, for his beloved Edmund had left England at a point between Dover and Sandwich. Boniface of Savoy, Edmund's successor as Archbishop, invited him to be his Chancellor. It is not known why nothing came of the invitation. It could be that Richard refused. Ralph Nevill, Bishop of Chichester, died in 1244. The Chapter proposed as his successor, Robert Passelew, a prominent King's clerk, but Archbishop Boniface quashed the election on the grounds that Passelew had only moderate learning and Undistinguished morals. A meeting of bishops, presided over by Boniface and attended by Grosseteste, unanimously elected Richard heard of his election with mixed feelings. He saw that by refusing he could continue to live a peaceful and agreeable life, and that by accepting he was exposing himself to the same frustrations and persecutions as he had seen Edmund endure. In the end, he decided that the interests of the Church, and the fight for its freedom must come first. He summed the position up very succinctly: 'The only time you can accept a bishopric is when it is obviously going to make life more difficult'.

The King was furious when he heard of Richard's election. He considered Richard his personal enemy since he had been Edmund's friend. In spite, he refused to approve the election or to surrender the temporalities of the See which, according to custom, had reverted to him during the interregnum. Richard had no way open to him but appeal to the Pope, who was at Lyons for the Council. The King sent messengers to plead for the validity of Passelew's election, but the Pope decided in Richard's favour and himself consecrated him bishop. Other bishops were being consecrated that day, and the story is told that when the Pope was consecrating them, the sacred oil flowed from the amorphora only drop by drop, but that when he came to Richard it flowed in copious streams! On his way home, Richard visited the tomb of Edmund at Pontigny. The King's reactions to the Pope's decision were again violent. He still refused to surrender the manor's and the revenue of the See of Chichester. He forbade Richard entry to his Cathedral, and issued an edict forbidding any of his subjects to assist Richard in any way, even by giving him food or shelter. Richard does not seem to have been depressed. He consoled his Chapter with the quotation: 'Your sorrow shall be turned into joy'. and went to live with Simon, a priest in a poor benefice at Tarring, his people in their homes and ministering to them, and dug Simon's fig orchard. A comment by his medieval biographer deserves to be recorded, if only because we could so easily make it ourselves: 'Here he was, 50 years old, and not able to stretch his legs under his own table'. It could not have been an uncongenial life for Richard, but for the good of the Church of Chichester he could not allow it to continue. For one thing, as he said, the King was wasting on his favourites money which should be given to the poor.

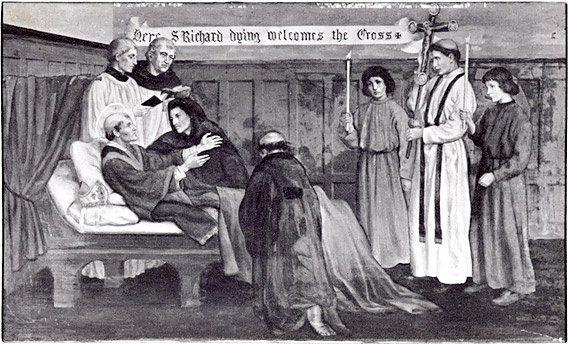

The impasse dragged on for two years and was resolved only when the Pope threatened to place the whole of England under an interdict. Henry yielded, and Richard took possession of his See. It remained a source of contention between them that Henry never made restitution of the revenue he had unlawfully withheld. Even in his Will Richard wrote, 'I will also that, for the fulfillment of the foregoing, there be demanded by my executors from my lord the King the profits arising from the Bishopric of Chichester, which he for two years unjustly took, and which of right belong to me, for concerning them, I will require the payment before the Most High, unless he shall have satisfied my executors according to their wish'. Even so, King Henry did nothing, but Edward I, in a deed dated at Chichester, at the time of the translation of St Richard in 1726, recites, 'that the debt of two hundred pounds which had been lent to King Henry by the Bishop (as he deliberately describes the transaction), had been, after dispute, now fully paid to the executors, William de Selsey and Robert de Purle, for the unburthening of the soul of my said father, as was right to do'. Richard led a life of austere penance, but he was kind and generous, especially to the poor. He was the despair of Willard, his cook, and of Hugh, who looked after his clothes. Food, clothes, horses, silverware, were given endlessly to the poor. His own food would be a piece of bread, dipped in wine. He had a great love of animals, especially little animals. Stories of little birds abound in the early accounts of his life. One feels that he was not just teasing Willard on the occasion when he served a brace of birds at table: 'Poor little innocents, what have you done to deserve death. If you could speak, you would accuse us of gluttony.' This is not the place to tell all the anecdotes and legends about Richard, neither is it the place to tell of his miracles. He continued to visit his diocese on foot, and share their lot with the peasants and the fishermen. He is the nearest the English Church has come to producing a Francis of Assisi. Typical of him would be his remark to the birds the day he slept in: 'Today you have been up before this lazybones, to sing your praises to our Creator'. Mention has already been made of his death in Dover.

His body was taken back to Chichester. It was a triumphal journey. Through all the villages and towns on the way, church bells rang 'both in sorrow and in joy', and the peasants and the poor thronged the route. At Chichester, he was buried, as he had requested, in the nave of the Cathedral 'in humble grave near the alter of St Edmund, hard over by the column'. After he was canonized in January 1262, his grave was considered too simple, and plans were made to transfer his body to a more worthy shrine. The plans were not put into immediate effect on account of the Baron's War, but on 16th June 1276 the translation took place. His shrine was behind the High Altar. Chichester became one of the most famous shrines in England, so that in 1478 special regulations had to be introduced to speed the flow of pilgrims. Thomas Cromwell signed, in the the name of King Henry VIII, the Commission for the destruction of the shrine on 14th NOvember 1538. All the silver, gold, jewels, ornaments and plate were to be taken to the Tower of London for safe keeping, and the shrine itself was 'to be razed and defaced to the very ground'. Cromwell's men did the razing and defacing on 20th November. They worked by night for fear of being attacked by people. What became of St Richard's body is not recorded, but that last act was to no one's honour. |

|